Although the majority of the Camp Lejeune wounded warriors claim the title "Marine," a few of the residents prefer the nickname "Doc." Hospitalman first class (HM1) Glenn Minney is one of the few sailors who've come to call the wounded warrior barracks their home. A Navy reservist, Minney enlisted in 1985. "Doc" Minney was activated and deployed to Iraq in January, 2005. While serving with 3rd Battalion, 25th Marine Regiment, he was wounded by mortar shrapnel while standing atop the Haditha Dam, a 10 story high facility that serves as a Forward Operating Base for Marines and Corpsman stationed near the Euphrates River Valley. "It was a typical, hot day in Iraq. I had to go out to one of the CONEX boxes to get supplies for the Battalion Aid Station...and the dam came under mortar attack. I was out on the 10th deck on a catwalk and a mortar round went off about 30 feet in front of me." HM1 Minney remembered running back inside the dam, the unit going to General Quarters as four additional rounds exploded near the dam. At the time, he did not know he was injured. "My vision was a little blurry and I had a severe headache, but I didn't think much of it," Minney stated. The next day, however, his eyes started bothring him, and he began receiving treatments for pink-eye. Unknown to the "Doc", however, both retinas in his eyes had become detached from the concussion of the blast. Blood vessels had ruptured, allowing the vitrouse fluids to leak from his eyes. "I started developing tunnel vision, and it was slowly closing in, becoming pinpoint. I talked to my Battalion Surgeon, and sat him down in private and told him 'I am going blind'." Medevac'd to Al Asad, then to Balad, an opthamologist recommended immediate evacuation to Hamburg, Germany for surgery. His first surgery lasted 3 hours, and he received two more operations before heading home to the United States. On September 2, 2005, while convalescing at home, his vision again went black and he required additional emergency surgery. Still on active duty orders, he was offered the opportunity to move into the wounded warrior barracks in the fall of 2005. "At times, you can't talk to your spouse, your mother, your father, friends, about things they've never been exposed to. Being around people who've been there, and having the medical facility...that's the benefit to having the wounded warrior program. Care is first priorty, whether it be mental, physical or social - we go out of our way to hit all those avenues."

Although the majority of the Camp Lejeune wounded warriors claim the title "Marine," a few of the residents prefer the nickname "Doc." Hospitalman first class (HM1) Glenn Minney is one of the few sailors who've come to call the wounded warrior barracks their home. A Navy reservist, Minney enlisted in 1985. "Doc" Minney was activated and deployed to Iraq in January, 2005. While serving with 3rd Battalion, 25th Marine Regiment, he was wounded by mortar shrapnel while standing atop the Haditha Dam, a 10 story high facility that serves as a Forward Operating Base for Marines and Corpsman stationed near the Euphrates River Valley. "It was a typical, hot day in Iraq. I had to go out to one of the CONEX boxes to get supplies for the Battalion Aid Station...and the dam came under mortar attack. I was out on the 10th deck on a catwalk and a mortar round went off about 30 feet in front of me." HM1 Minney remembered running back inside the dam, the unit going to General Quarters as four additional rounds exploded near the dam. At the time, he did not know he was injured. "My vision was a little blurry and I had a severe headache, but I didn't think much of it," Minney stated. The next day, however, his eyes started bothring him, and he began receiving treatments for pink-eye. Unknown to the "Doc", however, both retinas in his eyes had become detached from the concussion of the blast. Blood vessels had ruptured, allowing the vitrouse fluids to leak from his eyes. "I started developing tunnel vision, and it was slowly closing in, becoming pinpoint. I talked to my Battalion Surgeon, and sat him down in private and told him 'I am going blind'." Medevac'd to Al Asad, then to Balad, an opthamologist recommended immediate evacuation to Hamburg, Germany for surgery. His first surgery lasted 3 hours, and he received two more operations before heading home to the United States. On September 2, 2005, while convalescing at home, his vision again went black and he required additional emergency surgery. Still on active duty orders, he was offered the opportunity to move into the wounded warrior barracks in the fall of 2005. "At times, you can't talk to your spouse, your mother, your father, friends, about things they've never been exposed to. Being around people who've been there, and having the medical facility...that's the benefit to having the wounded warrior program. Care is first priorty, whether it be mental, physical or social - we go out of our way to hit all those avenues."

The Daily Grind served as my personal journal during previous military deployments to Iraq. Dormant for some time, I've dusted it off for my latest deployment to Afghanistan. The posts contained herein are solely based on my personal observations and do not represent the official views of the U.S. Marine Corps.

Thursday, October 26, 2006

The Men and Their Stories - Wounded Part 4 (Final)

Although the majority of the Camp Lejeune wounded warriors claim the title "Marine," a few of the residents prefer the nickname "Doc." Hospitalman first class (HM1) Glenn Minney is one of the few sailors who've come to call the wounded warrior barracks their home. A Navy reservist, Minney enlisted in 1985. "Doc" Minney was activated and deployed to Iraq in January, 2005. While serving with 3rd Battalion, 25th Marine Regiment, he was wounded by mortar shrapnel while standing atop the Haditha Dam, a 10 story high facility that serves as a Forward Operating Base for Marines and Corpsman stationed near the Euphrates River Valley. "It was a typical, hot day in Iraq. I had to go out to one of the CONEX boxes to get supplies for the Battalion Aid Station...and the dam came under mortar attack. I was out on the 10th deck on a catwalk and a mortar round went off about 30 feet in front of me." HM1 Minney remembered running back inside the dam, the unit going to General Quarters as four additional rounds exploded near the dam. At the time, he did not know he was injured. "My vision was a little blurry and I had a severe headache, but I didn't think much of it," Minney stated. The next day, however, his eyes started bothring him, and he began receiving treatments for pink-eye. Unknown to the "Doc", however, both retinas in his eyes had become detached from the concussion of the blast. Blood vessels had ruptured, allowing the vitrouse fluids to leak from his eyes. "I started developing tunnel vision, and it was slowly closing in, becoming pinpoint. I talked to my Battalion Surgeon, and sat him down in private and told him 'I am going blind'." Medevac'd to Al Asad, then to Balad, an opthamologist recommended immediate evacuation to Hamburg, Germany for surgery. His first surgery lasted 3 hours, and he received two more operations before heading home to the United States. On September 2, 2005, while convalescing at home, his vision again went black and he required additional emergency surgery. Still on active duty orders, he was offered the opportunity to move into the wounded warrior barracks in the fall of 2005. "At times, you can't talk to your spouse, your mother, your father, friends, about things they've never been exposed to. Being around people who've been there, and having the medical facility...that's the benefit to having the wounded warrior program. Care is first priorty, whether it be mental, physical or social - we go out of our way to hit all those avenues."

Although the majority of the Camp Lejeune wounded warriors claim the title "Marine," a few of the residents prefer the nickname "Doc." Hospitalman first class (HM1) Glenn Minney is one of the few sailors who've come to call the wounded warrior barracks their home. A Navy reservist, Minney enlisted in 1985. "Doc" Minney was activated and deployed to Iraq in January, 2005. While serving with 3rd Battalion, 25th Marine Regiment, he was wounded by mortar shrapnel while standing atop the Haditha Dam, a 10 story high facility that serves as a Forward Operating Base for Marines and Corpsman stationed near the Euphrates River Valley. "It was a typical, hot day in Iraq. I had to go out to one of the CONEX boxes to get supplies for the Battalion Aid Station...and the dam came under mortar attack. I was out on the 10th deck on a catwalk and a mortar round went off about 30 feet in front of me." HM1 Minney remembered running back inside the dam, the unit going to General Quarters as four additional rounds exploded near the dam. At the time, he did not know he was injured. "My vision was a little blurry and I had a severe headache, but I didn't think much of it," Minney stated. The next day, however, his eyes started bothring him, and he began receiving treatments for pink-eye. Unknown to the "Doc", however, both retinas in his eyes had become detached from the concussion of the blast. Blood vessels had ruptured, allowing the vitrouse fluids to leak from his eyes. "I started developing tunnel vision, and it was slowly closing in, becoming pinpoint. I talked to my Battalion Surgeon, and sat him down in private and told him 'I am going blind'." Medevac'd to Al Asad, then to Balad, an opthamologist recommended immediate evacuation to Hamburg, Germany for surgery. His first surgery lasted 3 hours, and he received two more operations before heading home to the United States. On September 2, 2005, while convalescing at home, his vision again went black and he required additional emergency surgery. Still on active duty orders, he was offered the opportunity to move into the wounded warrior barracks in the fall of 2005. "At times, you can't talk to your spouse, your mother, your father, friends, about things they've never been exposed to. Being around people who've been there, and having the medical facility...that's the benefit to having the wounded warrior program. Care is first priorty, whether it be mental, physical or social - we go out of our way to hit all those avenues."

Monday, October 23, 2006

The Men and Their Stories - Wounded Part 3

LCpl. Peter Dmitruk, an 0311 with Kilo Company, 3rd Battalion, 6th Marine Regiment, arrived at the Wounded Warrior barracks in September, 2005. Having graduated from boot camp less than one year earlier, he returned to Camp Lejeune with a career's worth of experience. Deployed to the Syrian border in the summer of 2005, LCpl. Dmitruk became accustomed to the daily grind of snap vehicle check points, presence patrols and security patrols around town. Having just returned from patrol to his company's battle position, he was reaching into his pack which he'd tossed atop the hescoe barrier that provided cover for him and his fellow Marines. "A mortar had fallen pretty close...I didn't hear the mortar, but I felt it. It felt like I kinda got punched. My arm flew up into my body. I looked down and it was mangled...kinda looked like it had gotten caught in a shredder. I could see the blood, which looked like arterial bleeding." A company corpsman laid him down and injected LCpl. Dmitruk with morphine. "I remember laying down on the stretcher, apologizing to everyone for getting hurt. I didn't want to leave." A medevac helicopter landed shortly thereafter and took him to the forward resuscitative surgical suite (FRSS) at FOB (forward operating base) Al Qaim. "I remember asking the Batalion Commander if I could stay...one of the medical officers (was) there; I could see he shook his head, so I knew I was going home. He said 'this is your time to heal, you've done what you can'." His injuries resulted in the introduction of a titanium plate into his arm, a necessity after losing nearly five inches of bone. Skin was grafted from his leg to cover the wounds and hasten the healing process. Following numerous surgeries, LCpl Dmitruk moved into the Wounded Warrior barracks in January, 2006 and has since realized the significance of living there, vice convalescing at home or in his unit's barracks. "I realized that when I'm here (in the wounded warrior barracks), healing is the number one priority...you'll always find a way to get to your appointments. That's the reason you're here, to heal and to get better."

LCpl. Peter Dmitruk, an 0311 with Kilo Company, 3rd Battalion, 6th Marine Regiment, arrived at the Wounded Warrior barracks in September, 2005. Having graduated from boot camp less than one year earlier, he returned to Camp Lejeune with a career's worth of experience. Deployed to the Syrian border in the summer of 2005, LCpl. Dmitruk became accustomed to the daily grind of snap vehicle check points, presence patrols and security patrols around town. Having just returned from patrol to his company's battle position, he was reaching into his pack which he'd tossed atop the hescoe barrier that provided cover for him and his fellow Marines. "A mortar had fallen pretty close...I didn't hear the mortar, but I felt it. It felt like I kinda got punched. My arm flew up into my body. I looked down and it was mangled...kinda looked like it had gotten caught in a shredder. I could see the blood, which looked like arterial bleeding." A company corpsman laid him down and injected LCpl. Dmitruk with morphine. "I remember laying down on the stretcher, apologizing to everyone for getting hurt. I didn't want to leave." A medevac helicopter landed shortly thereafter and took him to the forward resuscitative surgical suite (FRSS) at FOB (forward operating base) Al Qaim. "I remember asking the Batalion Commander if I could stay...one of the medical officers (was) there; I could see he shook his head, so I knew I was going home. He said 'this is your time to heal, you've done what you can'." His injuries resulted in the introduction of a titanium plate into his arm, a necessity after losing nearly five inches of bone. Skin was grafted from his leg to cover the wounds and hasten the healing process. Following numerous surgeries, LCpl Dmitruk moved into the Wounded Warrior barracks in January, 2006 and has since realized the significance of living there, vice convalescing at home or in his unit's barracks. "I realized that when I'm here (in the wounded warrior barracks), healing is the number one priority...you'll always find a way to get to your appointments. That's the reason you're here, to heal and to get better."

Tuesday, October 17, 2006

The Men and Their Stories - Wounded Part 2

Born and raised in Augusta, Georgia, LCpl Phillip Tussey enlisted in the Marine Corps in October, 2003. His first duty assignment with Kilo Company, 3rd Battalion, 8th Marine Regiment would prove to be his most memorable. Deployed to the city of Ramadi, Iraq in the winter of 2006, LCpl Tussey was on foot patrol in one of the most dangerous cities in Iraq when a sniper's bullet found its mark. "I felt something sting my leg. I tried to stand up...I fell to the ground, trying to get myself back up...I put my hand on my thigh and (pulling) my hand back, there was blood on my hand. I knew I'd been hit." The bullet had hit him inside his left thigh, 8 inches below his hip. Two fellow Marines picked up LCpl Tussey and put him in the back of a hardback HMMWV, his squad still under fire. Spent .50 cal cartiridges from the M-2 Browning machine gun atop the HMMWV turrent were hitting him in the face as the gunner provided covering fire to his squad. "They started medevac'ing me. There was only a driver and a gunner in there, so I picked up the radio and was calling the Staff Sergeant, telling him that we were up and that we needed to roll." Despite the pain from his shattered leg, LCpl Tussey remained conscious until he went into surgery at Charlie-med, Camp Ramadi's field surgical unit. Flying out of Ramadi the same evening, he traveled through Baghdad and Balad before flying to Germany, where he spent the following four days in a morphine induced haze. "They put a rod from my hip to my knee in my leg and two screws in my hip to hold the rod in place," described Tussey, who has endured numerous surgeries since his wounding. He's been at the Wounded Warrior barracks since June 28, 2005. "I can't really do much right now, because of the crutches," says LCpl Tussey, although he has not let his limited mobility keep him tied to the barracks. In July, 2006, he traveled to the National Naval Medical Center at Bethesda, MD with Lt. General Amos, former Commanding General of II MEF, to visit other wounded Marines and sailors returning from Iraq. Encountering a wounded Corpsman from own unit, Tussey recalled the Corpsman's comments upon seeing the unexpected visitors. "The (wounded) Corpsman that we knew couldn't thank us enough. He was so happy (to see us). He said 'you don't know what this means for y'all to come see me.' "

Born and raised in Augusta, Georgia, LCpl Phillip Tussey enlisted in the Marine Corps in October, 2003. His first duty assignment with Kilo Company, 3rd Battalion, 8th Marine Regiment would prove to be his most memorable. Deployed to the city of Ramadi, Iraq in the winter of 2006, LCpl Tussey was on foot patrol in one of the most dangerous cities in Iraq when a sniper's bullet found its mark. "I felt something sting my leg. I tried to stand up...I fell to the ground, trying to get myself back up...I put my hand on my thigh and (pulling) my hand back, there was blood on my hand. I knew I'd been hit." The bullet had hit him inside his left thigh, 8 inches below his hip. Two fellow Marines picked up LCpl Tussey and put him in the back of a hardback HMMWV, his squad still under fire. Spent .50 cal cartiridges from the M-2 Browning machine gun atop the HMMWV turrent were hitting him in the face as the gunner provided covering fire to his squad. "They started medevac'ing me. There was only a driver and a gunner in there, so I picked up the radio and was calling the Staff Sergeant, telling him that we were up and that we needed to roll." Despite the pain from his shattered leg, LCpl Tussey remained conscious until he went into surgery at Charlie-med, Camp Ramadi's field surgical unit. Flying out of Ramadi the same evening, he traveled through Baghdad and Balad before flying to Germany, where he spent the following four days in a morphine induced haze. "They put a rod from my hip to my knee in my leg and two screws in my hip to hold the rod in place," described Tussey, who has endured numerous surgeries since his wounding. He's been at the Wounded Warrior barracks since June 28, 2005. "I can't really do much right now, because of the crutches," says LCpl Tussey, although he has not let his limited mobility keep him tied to the barracks. In July, 2006, he traveled to the National Naval Medical Center at Bethesda, MD with Lt. General Amos, former Commanding General of II MEF, to visit other wounded Marines and sailors returning from Iraq. Encountering a wounded Corpsman from own unit, Tussey recalled the Corpsman's comments upon seeing the unexpected visitors. "The (wounded) Corpsman that we knew couldn't thank us enough. He was so happy (to see us). He said 'you don't know what this means for y'all to come see me.' "

Friday, October 13, 2006

The Men and Their Stories - Wounded Part 1

Corporal Aaron M. Shareno deployed to Iraq on July 18, 2005 with 2nd Battalion, 2nd Marine Regiment (2/2). Serving near the city of Karma, Iraq, Cpl. Shareno was 5 months into his deployment when he was wounded by a suicide vehicle-borne IED on December 14th, just 11 days before Christmas. His platoon had established fighting positions near a palm grove, approximately 25 meters from the edge of the road, when an insurgent drove his vehicle into the side of a 7 ton truck, detonating the explosives and instantly vaporizing the vehicle. The explosion sent shrapnel and chunks of metal through the air, knocking Cpl. Shareno and other Marines to the ground. "I got blown forward and a piece of shrapnel traveled through my palm and blew out the left matacarpal in my thumb - just shattered it," recalled Shareno. "When I got blown forward, I remember thinking I'm dead...I fell to my side and felt something was funny, not right...I saw my thumb drooping down...blood flowing out of my palm. It nicked two arteries in my hand. I put pressure on it below the wrist to stop the bleeding." Cpl. Shareno lauded the fast reaction of the Corpsman who treated him on the scene, but could not remember his name. "If I saw his face, I could recognize (him)", Shareno said. "He slapped a tournaquet on my hand...it was a unique experience." Medevac'd to Camp Fallujah Surgical, then ultimately to Balad and Germany before flying back to the United States, Cpl. Shareno regretted not being able to finish his deployment in Iraq. " I was a little shook up...more angry than anything...I (was) two months out (from leaving); ready to reenlist (when) I get hit. I just wanted to finish my pump, I wanted to reenlist and I wanted to continue on with my Marine Corps career." Now at the Wounded Warrior Barracks at Camp Lejeune, Cpl. Shareno is much less angry and is not letting his injuries get in the way of his career. "I plan on retiring from the Marine Corps," says Shereno. "I'm staying til I don't have fun anymore. Right now I'm having tons of fun."

Corporal Aaron M. Shareno deployed to Iraq on July 18, 2005 with 2nd Battalion, 2nd Marine Regiment (2/2). Serving near the city of Karma, Iraq, Cpl. Shareno was 5 months into his deployment when he was wounded by a suicide vehicle-borne IED on December 14th, just 11 days before Christmas. His platoon had established fighting positions near a palm grove, approximately 25 meters from the edge of the road, when an insurgent drove his vehicle into the side of a 7 ton truck, detonating the explosives and instantly vaporizing the vehicle. The explosion sent shrapnel and chunks of metal through the air, knocking Cpl. Shareno and other Marines to the ground. "I got blown forward and a piece of shrapnel traveled through my palm and blew out the left matacarpal in my thumb - just shattered it," recalled Shareno. "When I got blown forward, I remember thinking I'm dead...I fell to my side and felt something was funny, not right...I saw my thumb drooping down...blood flowing out of my palm. It nicked two arteries in my hand. I put pressure on it below the wrist to stop the bleeding." Cpl. Shareno lauded the fast reaction of the Corpsman who treated him on the scene, but could not remember his name. "If I saw his face, I could recognize (him)", Shareno said. "He slapped a tournaquet on my hand...it was a unique experience." Medevac'd to Camp Fallujah Surgical, then ultimately to Balad and Germany before flying back to the United States, Cpl. Shareno regretted not being able to finish his deployment in Iraq. " I was a little shook up...more angry than anything...I (was) two months out (from leaving); ready to reenlist (when) I get hit. I just wanted to finish my pump, I wanted to reenlist and I wanted to continue on with my Marine Corps career." Now at the Wounded Warrior Barracks at Camp Lejeune, Cpl. Shareno is much less angry and is not letting his injuries get in the way of his career. "I plan on retiring from the Marine Corps," says Shereno. "I'm staying til I don't have fun anymore. Right now I'm having tons of fun."

Tuesday, October 10, 2006

Wounded Warriors

In August, 2006, I had the honor of spending a week with 40 of our wounded Marines and sailors at the Wounded Warrior Barracks, Camp Lejeune, NC. All returned from Iraq sooner than expected, the result of a well-aimed sniper's bullet or the peppering blast of an IED. Despite their wounds, the Marines continue to march, all of them looking forward to the day they can join their comrades back in their old unit. Some, unfortunately, will never realize that dream, while others will return to duty for yet another tour in Iraq.

The photo shows Lieutenant General Amos (right), former Commanding General, II MEF, at the ribbon cutting ceremony of Maxwell Hall, the official designation for the wounded warrior barracks. LtCol Tim Maxwell, himself recovering from wounds in Iraq, stands atop the stairs with his wife and child. Tim is the mastermind behind the barracks concept and is owed credit for giving our wounded Marines a place they can call home during their recovery process. Here is my version of this success story:

Wounded Warriors

“My hands were in flames, and my whole face was in flames”, said Sgt. Jason Simms, recalling the fateful day in July, 2004 when his light armored vehicle was struck by the blast of an IED, or improvised explosive device. He was nearing the end of an 8 hour patrol with Delta Company, 2nd LAR Battalion, when his life changed forever.

“My hands suffered third degree burns…and my face took second degree burns. I took three bullets in the right leg, with shrapnel through my tendons and arteries” says Simms, sitting comfortably inside the II MEF wounded warrior barracks at Camp Lejeune, NC. Still recovering from his wounds, the Sergeant motions toward the passageway where Marines begin to congregate prior to their afternoon formation. “Everyone here has been wounded. I think the most important thing here is we were all wounded and we can all understand each other.”

The wounded warrior barracks is home to over 40 Marines and sailors of the II Marine Expeditionary Force, or II MEF. Located at Hospital Point aboard Camp Lejeune, the barracks formerly served as a bachelor officers quarters. In September, 2005, however, the BOQ was transformed into a home away from home for Marines and FMF corpsmen returning early from Iraq, their trip the courtesy of an Iraqi sniper or the blast of an IED. The newly renovated barracks provides the sailors and Marines a place to rehabilitate, allowing them to and focus on their medical needs rather than their next field evolution or unit training class.

The injured Marines and sailors are officially assigned to the Wounded Warrior Support Section, one of two sections comprised within the II MEF Injured Support Unit, or ISU. Established with the goal of tracking all injured II MEF service members and providing support to them and their immediate families, the ISU was developed in 2005, subsequent to a realization that some injured Marines and sailors were convalescing at home or within a variety of military and civilian medical centers, effectively cutting them off from their Marine Corps family.

Lieutenant General James F. Amos, former Commanding General of II MEF, recognized the need for a program that would track each and every wounded Marine and sailor coming home from the Middle East. Scribbling notes on personalized stationary, MajGen. Amos penned the following end state: "We will stay plugged in to every single wounded Marine who has been evacuated to CONUS for rehabilitation...until such time (sic) he no longer needs our assistance." According to the General's hand written memorandum, tracking and communication were the key elements that would lead to the successful formulation of the ISU. Later refining his end state by issuing a formal CG's intent, he wrote "I intend to develop an all encompassing program that provides continual support to all injured II MEF service members until such time as the service member no longer desires the support. This continual support will also extend to his or her immediate family. The program is directed to be a "one stop" shop for all injured II MEF service members, staffed with resident experts capable of finding solutions to all inquiries. It will provide continual command care and concern to the injured service member and their families throughout their transition to either continued military service or to the civilian community."

And so began the Injured Support Unit. Initially staffed with both recalled reservists and active duty personnel, its dedicated members made numerous liaison visits to wounded Marines in Military hospitals and VA centers across the country. Whether tracking the flight status of an injured service member from the time of injury until his return to CONUS, or assisting him in separating from active service, the ISU involves themselves in every facet of the Marines rehabilitative process to include the complicated logistics of family travel, convalescent leave, and follow-on medical treatment and rehabilitation, as well as VA transition and the medical evaluation process.

Since its inception, the ISU has tracked and assisted more than 2,000 wounded Marines and sailors. Unfortunately, not all of the injured Marines or sailors return to Camp Lejeune to rehabilitate among their fellow Marines and sailors. Many remain bed-ridden or continue to receive therapy at other locations, such as the National Naval Medical Center in Bethesda, Maryland or the military burn center at the Trauma Institute of San Antonio, Texas. Regardless of their location, the men and women of the ISU spend countless hours making telephone calls and personal visits to each and every Marine, ensuring no one falls through the cracks.

According to Major Daniel Hooker, Assistant OIC of the ISU, the unit quickly established a routine and developed primary points of contact at every hospital and trauma center known to treat wounded sailors and Marines. Referring to the ISU as the II MEF Chief of Staff's "hip pocket artillery" when it comes to injured support issues, Major Hooker emphasizes his primary goal: "Whenever we thought about the Commanders intent, it was simply, do we have an accurate list of the present physical location and contact information of all our wounded and are we actively helping them?"

"We have two main sections of the ISU" says Hooker. "The Injured Support Section...they handle the separate subsets of our wounded, which includes the medically discharged; the very seriously injured; the seriously injured; and the not seriously injured. The other main section is the wounded warrior barracks, also called the Wounded Warrior Support Section. In the barracks side, everyone has been wounded except the Lieutenant, while on the (ISS) side, no one has. Part of that was by design, in terms of the staff of the barracks. There could be very effective leadership and mentorship of wounded (Marines and sailors) by Officers and SNCO's that had also been wounded, in that they could serve as role models and could provide living proof that you can overcome your challenges, even severe wounds such as those LtCol. Maxwell sustained. He has served as an inspiration to the men, who in most cases, and as far as the residents of the barracks go, were less severely wounded than he was."

Major Hooker was referring to LtCol. Tim Maxwell, the Officer in Charge of the Wounded Warrior Support Section. As the chief advocate for the development of a medical rehabilitation platoon, a place where Marines and sailors could live in an environment shaped by their experiences in battle and their struggle to recuperate, LtCol. Maxwell was himself seriously wounded by an IED while serving as the Operations Officer for the 24th MEU. Shrapnel from the blast tore into his skull, leaving him with traumatic head and brain injuries. Unwilling to give up his struggle to stay Marine, he learned to walk, then talk, besieged by therapy and rehabilitation. Despite permanent damage he suffered, his injuries are relatively unnoticeable to the average person. He has since regained his speech and his health continues to improve with each passing day.

It was LtCol. Maxwell who first suggested the central billeting concept, a place of cohabitation for injured service members. In addition to enhancing the II MEF tracking capability, the central billeting concept would reduce the Marine's feeling of isolation and provide an environment for shared experiences, as well as creating an opportunity for smoother transition back to their unit or when separating from the Corps. Most importantly, the barracks would provide a consolidated location where specialized services, medical oversight, and morale enhancements could be offered under one roof for the collective benefit of all wounded service members. Maxwell summarized his idea - "The concept was simple...let's just keep the guys together, so they don't have to spend time alone."

LtCol. Maxwell's cadre wear many hats while working in the barracks. They serve as ad hoc parents, mentors and role models, all but one having been wounded in the war on terrorism. "The units are not set up to help some of these Marines who need long term care, but (who) are not going to stay in a hospital...it's a full time job doing that," mentions Gunnery Sgt. Barnes, Staff NCOIC of the Wounded Warrior Support Section. Pondering the benefits of the wounded warrior barracks, Gunnery Sgt. Barnes finds merit in the collective healing concept. "It's something I know because of all the doctors appointments (I required) and the amount of drugs I took for awhile," Barnes explains. "It's not a unit's lack of compassion or understanding, it's a lack of time to focus on those issues. Units don't have anything dedicated or set up to take the young Marines to their hospital appointments. Their hearts are in the right place...they want to be able to do that, but they have one focus when they get back, and it's not to heal...it's to rebuild and to get the unit ready to fight again."

Gunnery Sgt. Barnes stresses the wounded Marines aren't babied at the barracks. "I only give them compassion when they need compassion. I don't feel sorry for them because they got hurt...I got hurt. I don't expect anyone to feel sorry for me, either. If you need help getting your pant leg on, well...that's not something you need to feel sorry for anybody for. It's just something you need help with...it shouldn't be embarrassing. You're still going to have to look good in your Alphas. They are required to be at work. We have a ton of jobs we get them involved in. The sergeants I've got here are squad leaders; they work around their doctors appointments. It shows them they can still do it."

Resembling little like the billeting at their parent unit, the wounded warrior barracks provides its inhabitants with private rooms, complete with individual bathrooms and separate living space. The barracks itself is modified with handicapped ramps and wheelchair accessible entry points. The barracks personnel were recently provided a beautiful stainless steel propane grill from the 2nd Marine Division Association, now permanently installed outside the barracks entrance. More important than its physical features, however, the barracks offers the wounded a place to share their experiences with others who’ve endured the same hardships and who share the same need for additional surgery and treatment.

"It's almost like being in Iraq" says LCpl. Brandon Love, a SAW gunner for 2nd BN, 2nd Marine Regiment who suffered severe shrapnel wounds in Al Karma, Iraq in September, 2005. "You find out about these guys...everybody has seen combat. Most everybody has seen their buddies get injured if not killed, and everybody here was injured. Those three things make us more alike than most people realize, regardless of where we are from, what our MOS is...the brotherhood and the camaraderie is the most beneficial thing." LCpl. Love's comments were quickly echoed by LCpl. Bruce Schweitzer, injured in March, 2006 while serving with 3/8 in Ramadi, Iraq, "They focus completely on your injury. It's all about your injury. They want to get you healed up and get you back with your unit."

General Michael Hagee, Commandant of the Marine Corps, had this to say to the staff of MARINES, the Corps Official Magazine in September, 2005. "Our Marines are just that; Marines to the core. Some have lost limbs or sustained other types of serious injuries, but amazingly they're trying to recover as quickly as possible so they can get back to their units. They don't slow down when thrown a curve ball and their resiliency and determination are breathtaking. When I talk to one of these Marines and they explain how they want to continue with their service, I want to make sure the Marine Corps takes the right steps to make that happen." Apparently, II MEF has taken the first steps and is continuing to march.

Wednesday, September 27, 2006

The Best and Worst of Iraq, Marine style...

A Marine Intel Officer in Al Anbar Shares Some Thoughts

From the net...courtesy of Reads...

Classification: UNCLASSIFIED

All: I haven’t written very much from Iraq. There’s really not much to write about. More exactly, there’s not much I can write about because practically everything I do, read or hear is classified military information or is depressing to the point that I’d rather just forget about it, never mind write about it. The gaps in between all of that are filled with the pure tedium of daily life in an armed camp. So it’s a bit of a struggle to think of anything to put into a letter that’s worth reading. Worse, this place just consumes you. I work 18-20-hour days, every day. The quest to draw a clear picture of what the insurgents are up to never ends. Problems and frictions crop up faster than solutions. Every challenge demands a response. It’s like this every day. Before I know it, I can’t see straight, because it’s 0400 and I’ve been at work for twenty hours straight, somehow missing dinner again in the process. And once again I haven’t written to anyone. It starts all over again four hours later. It’s not really like Ground Hog Day, it’s more like a level from Dante’s Inferno.

Rather than attempting to sum up the last seven months, I figured I’d just hit the record setting highlights of 2006 in Iraq. These are among the events and experiences I’ll remember best.

Worst Case of Déjà Vu - I thought I was familiar with the feeling of déjà vu until I arrived back here in Fallujah in February. The moment I stepped off of the helicopter, just as dawn broke, and saw the camp just as I had left it ten months before - that was déjà vu. Kind of unnerving. It was as if I had never left. Same work area, same busted desk, same chair, same computer, same room, same creaky rack, same . . . everything. Same everything for the next year. It was like entering a parallel universe. Home wasn’t 10,000 miles away, it was a different lifetime.

Most Surreal Moment - Watching Marines arrive at my detention facility and unload a truck load of flex-cuffed midgets. 26 to be exact. I had put the word out earlier in the day to the Marines in Fallujah that we were looking for Bad Guy X, who was described as a midget. Little did I know that Fallujah was home to a small community of midgets, who banded together for support since they were considered as social outcasts. The Marines were anxious to get back to the midget colony to bring in the rest of the midget suspects, but I called off the search, figuring Bad Guy X was long gone on his short legs after seeing his companions rounded up by the giant infidels.

Most Profound Man in Iraq - an unidentified farmer in a fairly remote area who, after being asked by Reconnaissance Marines (searching for Syrians) if he had seen any foreign fighters in the area replied “Yes, you.”

Worst City in al-Anbar Province - Ramadi, hands down. The provincial capital of 400,000 people. Killed over 1,000 insurgents in there since we arrived in February. Every day is a nasty gun battle. They blast us with giant bombs in the road, snipers, mortars and small arms. We blast them with tanks, attack helicopters, artillery, our snipers (much better than theirs), and every weapon that an infantryman can carry. Every day. Incredibly, I rarely see Ramadi in the news. We have as many attacks out here in the west as Baghdad. Yet, Baghdad has 7 million people, we have just 1.2 million. Per capita, al-Anbar province is the most violent place in Iraq by several orders of magnitude. I suppose it was no accident that the Marines were assigned this area in 2003.

Bravest Guy in al-Anbar Province - Any Explosive Ordnance Disposal Technician (EOD Tech). How’d you like a job that required you to defuse bombs in a hole in the middle of the road that very likely are booby-trapped or connected by wire to a bad guy who’s just waiting for you to get close to the bomb before he clicks the detonator? Every day. Sanitation workers in New York City get paid more than these guys. Talk about courage and commitment.

Second Bravest Guy in al-Anbar Province - It’s a 20,000 way tie among all the Marines and Soldiers who venture out on the highways and through the towns of al-Anbar every day, not knowing if it will be their last - and for a couple of them, it will be.

Best Piece of U.S. Gear - new, bullet-proof flak jackets. O.K., they weigh 40 lbs and aren’t exactly comfortable in 120 degree heat, but they’ve saved countless lives out here.

Best Piece of Bad Guy Gear - Armor Piercing ammunition that goes right through the new flak jackets and the Marines inside them.

Worst E-Mail Message - “The Walking Blood Bank is Activated. We need blood type A+ stat.” I always head down to the surgical unit as soon as I get these messages, but I never give blood - there’s always about 80 Marines in line, night or day.

Biggest Surprise - Iraqi Police. All local guys. I never figured that we’d get a police force established in the cities in al-Anbar. I estimated that insurgents would kill the first few, scaring off the rest. Well, insurgents did kill the first few, but the cops kept on coming. The insurgents continue to target the police, killing them in their homes and on the streets, but the cops won’t give up. Absolutely incredible tenacity. The insurgents know that the police are far better at finding them than we are. - and they are finding them. Now, if we could just get them out of the habit of beating prisoners to a pulp . . .

Greatest Vindication - Stocking up on outrageous quantities of Diet Coke from the chow hall in spite of the derision from my men on such hoarding, then having a 122mm rocket blast apart the giant shipping container that held all of the soda for the chow hall. Yep, you can’t buy experience.

Biggest Mystery - How some people can gain weight out here. I’m down to 165 lbs. Who has time to eat?

Second Biggest Mystery - if there’s no atheists in foxholes, then why aren’t there more people at Mass every Sunday?

Favorite Iraqi TV Show - Oprah. I have no idea. They all have satellite TV.

Coolest Insurgent Act - Stealing almost $7 million from the main bank in Ramadi in broad daylight, then, upon exiting, waving to the Marines in the combat outpost right next to the bank, who had no clue of what was going on. The Marines waved back. Too cool.

Most Memorable Scene - In the middle of the night, on a dusty airfield, watching the better part of a battalion of Marines packed up and ready to go home after six months in al-Anbar, the relief etched in their young faces even in the moonlight. Then watching these same Marines exchange glances with a similar number of grunts loaded down with gear file past - their replacements. Nothing was said. Nothing needed to be said.

Highest Unit Re-enlistment Rate - Any outfit that has been in Iraq recently. All the danger, all the hardship, all the time away from home, all the horror, all the frustrations with the fight here - all are outweighed by the desire for young men to be part of a 'Band of Brothers' who will die for one another. They found what they were looking for when they enlisted out of high school. Man for man, they now have more combat experience than any Marines in the history of our Corps.

Most Surprising Thing I Don’t Miss - Beer. Perhaps being half-stunned by lack of sleep makes up for it.

Worst Smell - Porta-johns in 120 degree heat - and that’s 120 degrees outside of the porta-john.

Highest Temperature - I don’t know exactly, but it was in the porta-johns. Needed to re-hydrate after each trip to the loo.

Biggest Hassle - High-ranking visitors. More disruptive to work than a rocket attack. VIPs demand briefs and “battlefield” tours (we take them to quiet sections of Fallujah, which is plenty scary for them). Our briefs and commentary seem to have no affect on their preconceived notions of what’s going on in Iraq. Their trips allow them to say that they’ve been to Fallujah, which gives them an unfortunate degree of credibility in perpetuating their fantasies about the insurgency here.

Biggest Outrage - Practically anything said by talking heads on TV about the war in Iraq, not that I get to watch much TV. Their thoughts are consistently both grossly simplistic and politically slanted. Biggest offender - Bill O’Reilly - what a buffoon.

Best Intel Work - Finding Jill Carroll’s kidnappers - all of them. I was mighty proud of my guys that day. I figured we’d all get the Christian Science Monitor for free after this, but none have showed up yet. Talk about ingratitude.

Saddest Moment - Having the battalion commander from 1st Battalion, 1st Marines hand me the dog tags of one of my Marines who had just been killed while on a mission with his unit. Hit by a 60mm mortar. Cpl Bachar was a great Marine. I felt crushed for a long time afterward. His picture now hangs at the entrance to the Intelligence Section. We’ll carry it home with us when we leave in February.

Biggest Ass-Chewing - 10 July immediately following a visit by the Iraqi Deputy Prime Minister, Dr. Zobai. The Deputy Prime Minister brought along an American security contractor (read mercenary), who told my Commanding General that he was there to act as a mediator between us and the Bad Guys. I immediately told him what I thought of him and his asinine ideas in terms that made clear my disgust and which, unfortunately, are unrepeatable here. I thought my boss was going to have a heart attack. Fortunately, the translator couldn’t figure out the best Arabic words to convey my meaning for the Deputy Prime Minister. Later, the boss had no difficulty in conveying his meaning to me in English regarding my Irish temper, even though he agreed with me. At least the guy from the State Department thought it was hilarious. We never saw the mercenary again.

Best Chuck Norris Moment - 13 May. Bad Guys arrived at the government center in the small town of Kubaysah to kidnap the town mayor, since they have a problem with any form of government that does not include regular beheadings and women wearing burqahs. There were seven of them. As they brought the mayor out to put him in a pick-up truck to take him off to be beheaded (on video, as usual), one of the bad Guys put down his machinegun so that he could tie the mayor’s hands. The mayor took the opportunity to pick up the machinegun and drill five of the Bad Guys. The other two ran away. One of the dead Bad Guys was on our top twenty wanted list. Like they say, you can’t fight City Hall.

Worst Sound - That crack-boom off in the distance that means an IED or mine just went off. You just wonder who got it, hoping that it was a near miss rather than a direct hit. Hear it every day.

Second Worst Sound - Our artillery firing without warning. The howitzers are pretty close to where I work. Believe me, outgoing sounds a lot like incoming when our guns are firing right over our heads. They’d about knock the fillings out of your teeth.

Only Thing Better in Iraq Than in the U.S. - Sunsets. Spectacular. It’s from all the dust in the air.

Proudest Moment - It’s a tie every day, watching my Marines produce phenomenal intelligence products that go pretty far in teasing apart Bad Guy operations in al-Anbar. Every night Marines and Soldiers are kicking in doors and grabbing Bad Guys based on intelligence developed by my guys. We rarely lose a Marine during these raids, they are so well-informed of the objective. A bunch of kids right out of high school shouldn’t be able to work so well, but they do.

Happiest Moment - Well, it wasn’t in Iraq. There are no truly happy moments here. It was back in California when I was able to hold my family again while home on leave during July.

Most Common Thought - Home. Always thinking of home, of Kathleen and the kids. Wondering how everyone else is getting along. Regretting that I don’t write more. Yep, always thinking of home.

Friday, August 04, 2006

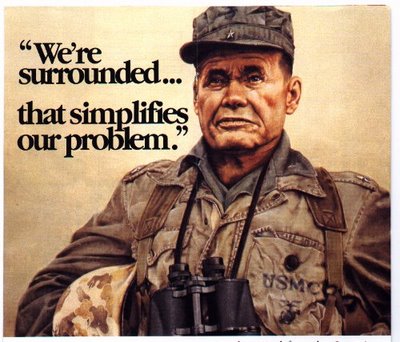

"We're surrounded - that simplifies our problem!"

When an Army Captain asked him for the direction of the line of retreat, Col Puller called his Tank Commander, gave them the Army position, and ordered: "If they start to pull back from that line, even one foot, I want you to open fire on them." Turning to the Captain, he replied "Does that answer your question? We're here to fight."

- Chesty Puller At Koto-ri in Korea

Lewis Burwell Puller, a native of West Point, Virginia, enlisted in the Marine Corps in 1917, shortly after completing his "rat year" at the Virginia Military Institute. Yearning to join the fight in Europe, he left his VMI classmates behind and attended Marine Corps recruit training, hoping to join the fight against the Germans. Unfortunately, he never saw combat during the world war and was placed on the Marine Corps inactive list due to post war drawdowns. Unsatisfied with civilian life, he re-enlisted in the Corps and got his first taste of combat in Haiti. It was the begining of a long line of military campaigns in which he'd participate. By the end of his 37 year career, Lt. General Lewis "Chesty" Puller had earned 14 personal decorations, to include five Navy Crosses, the Distinguished Service Cross, the Silver Star, two Legions of Merit with "V" device, the Bronze Star with "V" device, the Air Medal and the Purple Heart.

"Chesty" Puller became more than a hero; he was an American legend. His gruff, give 'em hell attitude was admired throughout the Marine Corps. His bravery and his nickname were known to millions of Americans on the home front. He was a man's man, a Marine' s Marine. For all his renown, however, there are few permanent monuments to "Chesty" Puller. One of the few is in the Hall of Valor at the VMI Museum. There, thousands of visitors come each year to learn about the VMI men who've made our nation great. "Chesty" Puller's medals are on display along with those of other famous VMI graduates, to include Admiral Richard E. Byrd, General Lemuel C. Shepherd, and others. Even some students who didn't graduate, such as General George Patton, lamented on VMI until the day they died. (paragraph courtesy of http://www.polaris.net/~jrube/chestpul.htm)

On June 29th, I was honored to assist the Marine Corps Museum with the retrieval of several dozen personal items belonging to LtGen. Puller. The items, located at the Marine Barracks at Naval Weapons Station, Yorktown, VA, included a complete set of the General's personal decorations, his original promotion warrants, an engraved Mameluke sword, a satin Lieutenant General's flag, and other items loaned to the Barracks in the mid 1970's by Mrs. Virginia Evans Puller, Chesty's widow. Displayed in "Puller Hall," the items have been remained in Yorktown for thirty years.

On June 29th, I was honored to assist the Marine Corps Museum with the retrieval of several dozen personal items belonging to LtGen. Puller. The items, located at the Marine Barracks at Naval Weapons Station, Yorktown, VA, included a complete set of the General's personal decorations, his original promotion warrants, an engraved Mameluke sword, a satin Lieutenant General's flag, and other items loaned to the Barracks in the mid 1970's by Mrs. Virginia Evans Puller, Chesty's widow. Displayed in "Puller Hall," the items have been remained in Yorktown for thirty years. In February, 2006, Ms. Puller passed away at the age of 97. At the request of the Puller family, the Marine Corps Museum began efforts to account for items that had been loaned to the Marine Corps by Ms. Puller and distributed among various Marine Corps commands. Working closely with the Yorktown Marine Corps Security Force Company Commander and XO, the Marine Corps Museum curator obtained a complete list of items displayed at Puller Hall and tentatively arranged to have the items transferred to the Museum on behalf of the Puller family. By June, the only task remaining was the retrieval and subsequent transfer of the items from Yorktown to Quantico.

In February, 2006, Ms. Puller passed away at the age of 97. At the request of the Puller family, the Marine Corps Museum began efforts to account for items that had been loaned to the Marine Corps by Ms. Puller and distributed among various Marine Corps commands. Working closely with the Yorktown Marine Corps Security Force Company Commander and XO, the Marine Corps Museum curator obtained a complete list of items displayed at Puller Hall and tentatively arranged to have the items transferred to the Museum on behalf of the Puller family. By June, the only task remaining was the retrieval and subsequent transfer of the items from Yorktown to Quantico. Sadly, the items had suffered the harmful effects of heat and sun damage while displayed at Puller Hall. Decoration ribbons had faded, as had photographs and flags that had become sun-baked behind the glass display case. Though beautifully displayed, the items were in need of restorative care, which will certainly occur once returned to the Museum. Assisted by the Marine Corps Security Force Supply Sgt., I carefully removed each item from the display case and packaged them in boxes, checking the items against the curator's list. Satisfied I had retrieved everything, I nervously departed the Weapons station with a priceless collection of artifacts in the back seat of my POV. As a fellow Marine and VMI alumnus, I 'm sure the General would have been satisfied to know I had been entrusted to care for his belongings, if only for 24 hours.

Sadly, the items had suffered the harmful effects of heat and sun damage while displayed at Puller Hall. Decoration ribbons had faded, as had photographs and flags that had become sun-baked behind the glass display case. Though beautifully displayed, the items were in need of restorative care, which will certainly occur once returned to the Museum. Assisted by the Marine Corps Security Force Supply Sgt., I carefully removed each item from the display case and packaged them in boxes, checking the items against the curator's list. Satisfied I had retrieved everything, I nervously departed the Weapons station with a priceless collection of artifacts in the back seat of my POV. As a fellow Marine and VMI alumnus, I 'm sure the General would have been satisfied to know I had been entrusted to care for his belongings, if only for 24 hours. Of all the items, my favorite artifact was Chesty's engraved mameluke sword, presented to the General in recognition of his valor in Haiti, where he'd served as an enlisted Marine with the Gendarmerie d'Haiti, a military force operating in Haiti under a treaty with the United States. Most of its officers were U. S. Marines, while its enlisted personnel were Haitians. Spending almost five years in Haiti, he saw frequent action against the Caco rebels before returning the the United States in 1924, where he was immediately commissioned a Marine second lieutenant. The sword was in beautiful condition, a truly significant piece among the Puller estate items.

Of all the items, my favorite artifact was Chesty's engraved mameluke sword, presented to the General in recognition of his valor in Haiti, where he'd served as an enlisted Marine with the Gendarmerie d'Haiti, a military force operating in Haiti under a treaty with the United States. Most of its officers were U. S. Marines, while its enlisted personnel were Haitians. Spending almost five years in Haiti, he saw frequent action against the Caco rebels before returning the the United States in 1924, where he was immediately commissioned a Marine second lieutenant. The sword was in beautiful condition, a truly significant piece among the Puller estate items.For those who weren't aware, the mameluke sword was originally adopted for wear by Marine Corps Officers after it was presented to Lieutenant Presley Neville O'Bannon, who led seven Marines and an odd assortment of mercenaries and cut-throats in a bayonet charge against a Tripoli fort on April 27, 1805, securing the surrender of Jessup, the bey of Tripoli. Hamet Karamanli promptly took as ruler of Tripoli and presented O'Bannon with his personal jeweled sword, the same type used by his Mameluke tribesmen. Today, Marine officers still carry this type of sword, commemorating the Corps' service during the Tripolitian War, 1801 - 05. Appropriately, the actions of O'Bannon and his small group of Marines are commemorated in the second line of the Marines' Hymn with the words, "To the Shores of Tripoli".

Arriving safely at the Marine Corps Museum, I gently unpacked and inventoried the items with Ms. Jennifer Castro, the museum curator and caretaker for the incredible assortment of artifacts held in the museum archives. In addition to her curator responsibilities, Jennifer is heavily engaged with the Marine Corps Heritage Foundation's National Museum of the Marine Corps, which will open on the 231st birthday of the Corps on Nov. 11, 2006 - you may have seen it while driving on interstate 95 near Quantico and Dumfries. It will soon display historic memorabilia of Marines past and present, which may one day include the documents, flags, decorations and sword belonging to the General we know simply as "Chesty."

L-R: Virginia Puller Dabney, Senator Linda T. Puller, Martha Puller Downs, General James L. Jones, Mr. Gordon W. Wagner, and Major General Josiah Bunting III.

Tuesday, May 16, 2006

Protecting America's Heroes

Criminal investigations…foreign counterintelligence…polygraph exams…dignitary protection…these are just a few of the jobs performed by Marine Corps special agents of the Naval Criminal Investigative Service (NCIS).

Criminal investigations…foreign counterintelligence…polygraph exams…dignitary protection…these are just a few of the jobs performed by Marine Corps special agents of the Naval Criminal Investigative Service (NCIS).The NCIS is a unique federal law enforcement agency comprised of special agents, investigators, forensic experts, security specialists, analysts, and support personnel. Headquartered at the Navy Yard in Washington, D.C., it is the primary law enforcement and counterintelligence arm of the United States Department of the Navy. The NCIS maintains a worldwide presence – its special agents operate from 15 field offices, including one operational unit dedicated to counterespionage, and more than 140 individual locations around the globe.

As the investigative arm of the Department of the Navy and the Marine Corps, NCIS special agents deploy to locations most federal agencies fear to tread. You’ll find NCIS special agents serving aboard aircraft carriers or aboard the ships of an Expeditionary Strike Group (ESG). They currently serve among the Marines and sailors of the I Marine Expeditionary Force (MEF) in Iraq, as well as in Afghanistan and among the Marine expeditionary units (MEU) in the Atlantic and Pacific and Persian Gulf. Forward deployed to dozens of countries around the globe, NCIS special agents strive to prevent terrorism, to protect the secrets of the Navy and the Marine Corps, and to reduce crime through a proactive and highly regarded criminal investigative program.

Unknown to many Marines and civilians alike, a small cadre of Marines work alongside the civilian special agents. They carry the same badge, conduct the same investigations, and testify at the same court hearings. They are Marine special agents, a few men and women of NCIS who’ve been individually screened and selected to serve the Navy and Marine Corps in a unique and exciting capacity. Previously assigned to the Criminal Investigative Division (CID) office at a major Marine Corps installation, the Marine special agent, once selected, is assigned to an NCIS field office or resident agency, such as the

Unknown to many Marines and civilians alike, a small cadre of Marines work alongside the civilian special agents. They carry the same badge, conduct the same investigations, and testify at the same court hearings. They are Marine special agents, a few men and women of NCIS who’ve been individually screened and selected to serve the Navy and Marine Corps in a unique and exciting capacity. Previously assigned to the Criminal Investigative Division (CID) office at a major Marine Corps installation, the Marine special agent, once selected, is assigned to an NCIS field office or resident agency, such as theCarolina Field Office located at and Camp Lejeune, N.C. or the Marine Marine Corps West Field

Office at Camp Pendleton, Calif.

Indistinguishable from a civilian special agent, the Marine special agents are treated as equals within the organization. Though technically employed by the Marine Corps, they no longer stand formation or uniform inspection. Instead, they stand duty, responding to crime scenes and engaging with commands who’ve fallen victim to a criminal act. They carry their own caseload of criminal or foreign counterintelligence investigations, working the cases from inception to prosecution. Often cooperating with other federal, state and local law enforcement agencies, the Marine special agents build a network of contacts and associates to further assist them in the conduct of their investigations.

According to Colonel John Forquer, the current military assistant to the NCIS Director and commanding officer of the NCIS Office of Military Support, roughly 65 Marine special agents and six counterintelligence Marines now fill the ranks of NCIS. They are joined by 130 Navy reservists and approximately 200 active-duty sailors performing various administrative, counterintelligence and analyst duties roles throughout the agency.

Despite the change in their working environment, the Marine special agents are still required to participate in PFTs, qualify with their firearms and meet the height and weight standards required of Marines in uniform. They still abide by professional military education requirements and are screened for promotion. Although they’ve traded their uniforms for a coat and tie, they remain Marines underneath and as such, are expected to meet the high standards of performance, physical readiness, and conduct.

With today’s demanding operational tempo, it is very likely that they will be deployed in support of potentially dangerous assignments and duties. Marine special agents were the some of the first NCIS special agents deployed to Iraq at the start of Operation Iraqi Freedom in 2003. From OIF I to present, over 32 former and current Marine special agents have deployed to Iraq to support the war on terrorism.

Leatherneck NCIS agents have conducted investigations into criminal misconduct of Marines and sailors, ranging from common theft incidents to sexual assaults. They’ve spent countless hours investigating non-combat related deaths and allegations of detainee abuse. They’ve embedded with other NCIS special agents at locations such as Camp Fallujah, Camp Blue Diamond, Tikrit, Taqaddum and Al Asad. Five Marine special agents are currently assigned to the 2006 deployment cycle in support of OIF and Operation Enduring Freedom in Afghanistan: Master Sergeant Tim Fowler,

Leatherneck NCIS agents have conducted investigations into criminal misconduct of Marines and sailors, ranging from common theft incidents to sexual assaults. They’ve spent countless hours investigating non-combat related deaths and allegations of detainee abuse. They’ve embedded with other NCIS special agents at locations such as Camp Fallujah, Camp Blue Diamond, Tikrit, Taqaddum and Al Asad. Five Marine special agents are currently assigned to the 2006 deployment cycle in support of OIF and Operation Enduring Freedom in Afghanistan: Master Sergeant Tim Fowler,Gunnery Sgt William Link, GySgt. Mark McLawhorn, SSgt Michael Payne and Sergeant Jeffrey Farmer.

Marine special agents have also served on personal protection teams in the cities of Al Hillah and Al Basra, protecting high-level dignitaries of the Coalition Provisional Authority (CPA) and the United Nations from potential threats and harm. Since the start of OIF, Marine special agents have subsequently deployed to Afghanistan, Kuwait, Bahrain, Djibouti and numerous other locations in the war against terrorism. First to fight, the Marine special agents are always at the tip of the NCIS spear.

MSgt Tim Fowler, a Marine special agent from the Washington Field Office, is an NCIS subject matter expert in the field of computer forensics and computer crime investigations. Deployed by NCIS to Iraq during OIF I, MSgt Fowler utilized the skills he practiced as a NCIS special agent to assist various governmental agencies with the screening of computer materials seized across the area of operations. Traveling across Iraq in a variety of military and civilian vehicles, his actions and incredible successes on the battlefield earned him a Bronze Star with combat “V”. MSgt Fowler is currently deployed with NCIS to Afghanistan in support of OEF, continuing the fight against terrorism.

MSgt Tim Fowler, Marine Special Agent, atop Mount Ghar, Afghanistan

GySgt Dan Carlin, a Marine special agent at the Carolinas Field Office, volunteered to serve on a dignitary protection team in the city of Al Hillah, Iraq during OIF 3. Part of a nine-man team dedicated to providing personal protection for the CPA ambassador in south central Iraq, “Gunny” Carlin often found himself dual-hated as a gunner and team navigator, using the land navigation skills he learned as a Marine to navigate around the small towns and villages between Baghdad and Hillah.

MSgt Patty Lyons, a Marine special agent from the NCIS Resident Agency in Quantico, deployed to Iraq in support of the NCIS criminal investigative mission, spending the bulk of her time with the Third Marine Aircraft Wing at Al Asad. Her assignment took her on dozens of “milk runs” aboard CH-46 Sea Knight and CH-53 Super Stallion helicopters to Al Asad, Taqaddum, and Camp Fallujah during her deployment, investigating crimes including arson, assault, bribery and graft.

Special Agent Doug Einsel, the supervisor for the NCIS detachment at Camp Fallujah, Iraq during OIF 4-6, said NCIS special agents, both Marine and civilian, are dedicated to supporting the MEF in Iraq, providing criminal investigative support and force protection methodology to the MEF. Working closely with the MEF antiterrorism/force protection (ATFP) cells and force-protection units established at each of the camps, the NCIS agents seek to identify physical and counterintelligence vulnerabilities which could jeopardize the health and well-being of Marines located at or transiting to the camps.

Formerly military police investigators (MOS 5819) or criminal investigators (MOS 5821), the Marine special agents receive their entry-level law enforcement training via the Marine Corps MOS training program at the Army’s Fort Leonard Wood, Missouri. Following their acceptance into NCIS, they are required to attend six weeks of specialized training conducted at the Federal Law Enforcement Training Center (FLETC) in Glynco, Georgia. Operated by the U.S. Department of Homeland Security, FLETC provides law-enforcement training to 81 partner agencies, to include the U.S. Marshals Service, the U.S. Secret Service, the U.S. Border Patrol, and the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms.

The newly selected Marine special agents learn the “ins and outs” of felony level investigations and how to operate in a civilian environment. They use this training time to sharpen their skills and to learn some advanced techniques for conducting crime scene examinations and interviews, enabling them manage a felony investigation from crime scene to courtroom.

For those special agents engaged in the war against terrorism, FLETC is creating a Counterterrorism Operations Training Facility to augment their already robust training center, situated on the grounds of the former Brunswick, Ga., Naval Air Station. The $50 million facility will recreate various settings, both foreign and domestic, that agents might encounter in the field, including urban and rural neighborhoods, subway stations, buildings and roadways. Within the facility, a mock Middle Eastern training village was constructed, providing students a realistic environment simulating the urban environment of Iraq. At least 13 organizations at FLETC, including NCIS, currently send graduates overseas in direct support of the war on terrorism.

Post academy training for both Marine and civilian special agents covers a variety of subjects, including but not limited to legal instruction, forensics, crime scene processing, firearms, driver training, computer crimes, illicit narcotics, child pornography, larceny, and a host of other activities prosecutable under the Uniform Code of Military Justice and the United States Code. If necessary, Marine special agents are granted relaxed grooming standards for certain activities, such as narcotics or gang investigations. Blending into their surroundings aboard base or out in town, the Marine special agents are an inseparable part of the NCIS team.

Seamlessly integrated into NCIS, the Marine special agents are enthusiastic about being part of the NCIS team. According to Col Forquer, the special agents in charge of the NCIS field offices are quick to tell you that the Marines assigned to the field offices are a critical part of their team. “They have an outstanding work ethic and eagerly take on the tough assignments. They are true professionals, absolutely dedicated to the mission. But if you asked a Marine special agent, he or she’d just tell you that it’s all in a days work.”

Leatherneck Editors Note: LtCol Covert served as one of two U.S. Marine Corps Field Historians deployed to Iraq during OIF 4-6. Traveling throughout the Al Anbar and Babil provinces, he collected 240 taped interviews of Marines, sailors and soldiers engaged in combat operations, security and stability operations (SASO) and combat service support. The interviews, along with corresponding photographs and documentary materials, are permanently archived at the Marine Corps Historical Division at Marine Corps Base Quantico, VA. In his civilian career, LtCol Covert is a Supervisory Special Agent for the Naval Criminal Investigative Service in Norfolk, VA.

Sunday, May 07, 2006

To the Border, Amigo

The following piece is a story I submitted to "Leatherneck" magazine for publication. I've been notified by the editor that it will probably appear in the August issue. For preview by fellow milbloggers and non-subscribers to Leatherneck, here's my first attempt at publication:

Standing upon the roof of a small border fort, five dust covered Marines scan the horizon, searching for signs of life across the sandy, barren desert. Joined by an equal number of Iraqi border police, the Marines and “jundee” discuss an upcoming patrol along the expansive border. The Marines belong to the Multi-National Forces West (MNF-W) border transition teams, or BTT, which operate along the Iraqi borders of Syria, Jordan, and Saudi Arabia.

Unique to OIF, the primary mission of the BTT Marines is to support the manning, training and equipping of the Iraqi Department of Border Enforcement, or DBE. One of several fledgling law enforcement organizations within the newly formed Iraqi Ministry of Interior (MOI), the DBE operates 43 border forts along 900 kilometers of border.

Tasked with staunching the flow of illegal aliens, foreign fighters, smugglers and insurgents into Iraq, the DBE remains a separate entity from their Iraqi Police (IP) counterparts, a separate law enforcement organization within the Ministry of Interior. Similar to the U.S. Border Patrol, the border policemen of the DBE exercise powers of arrest along the border, while the IP operate in the cities and towns located in the interior of the country.

Deploying to the border for weeks at a time, the BTT Marines work with and live among the Iraqi Jundees at the various forts. Supported by the addition of embedded Arabic interpreters, the BTT’s began their initial operations during the spring and summer of 2005. “Our job (was) to assess the operations and logistics at the forts, using the assessment as a baseline and trying to improve from there”, said Major Michael Casey, Border Transition Team Chief, during a September 2005 interview. “We spent a lot of time working with the jundees one on one, teaching leadership and basic military skills.” Classes on patrolling procedures, weapons maintenance and hygiene (were) routine. “We try to infuse the (warrior) ethos” Casey said.

The BTT Marines quickly found they had their hands full. “When we first got there, the area was the wild west,” said LtCol. Kenneth DeSimone, II MEF DBE coordinator from February through September, 2005. “We were told they (the Iraqi border police) were equipped and trained. But in reality, they had no uniforms, weapons, or vehicles. There was little or no comm – no radios or phones. It was a very spartan existence.” “It was straight from a scene out of an old French foreign legion film,” DeSimone continued. “Many of these forts are located in extremely desolate locations. The forts have turrets and shooting ports and look like miniature versions of a medieval castle. It may be the only real building within miles – there’s a surreal aspect to many of these locations.”

Prior to the arrival of the BTT Marines, few border forts had hosted permanent coalition staff. Some received sporadic visits from U.S. Army advisory support teams, as well as hosting officers of various U.S. civilian organizations such as the U.S. Border Patrol and U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) Agency. Assigned to remote areas like Waleed and Trebil, the officers deployed in 4-man teams, each comprised of two Border Patrolmen and 2 CBP Officers. Still, the lack of permanent coalition presence was a continuing issue.

Filling this void were the Marines of the BTT. Having Established the original Border Transition Teams by late spring, the Marines set out to assess the effectiveness of the existing Iraqi border police and to determine the readiness of their forts. Traveling hundreds of miles in small convoys, they moved in self-sufficient detachments initially containing M-1114 up-armored HMMWV’s (high mobility multi-purpose wheeled vehicle) and an accompanying logistics train comprised of a 7-ton MTVR (medium tactical vehicle replacement) or LVS (logistics vehicle system) filled with supplies and equipment.

The initial assessments uncovered a variety of challenges. The Iraqi border police typically relied on the leadership of border police officers to make the day-to-day decisions. Few, if any, leadership roles were delegated below the rank of officer and many of the border police failed to show for work on a routine basis. Sanitation concerns were almost non-existent at most forts and training was not being conducted on tactics, patrolling or standardized law enforcement techniques.

According to 1stLt. Braulio Lopez, logistics advisor for Border Transition Team 4 during OIF 4-6, the assessment phase paired up members of the BTT with individual policemen at the forts. The teams assessed not only the training and effectiveness of the border police, but also reviewed the maintenance of the buildings, the condition of their vehicles and the functionality of the weapons at the forts. Often lacking electricity, heat, water, and vehicles, the forts were initially ineffective.

One major obstacle hampering the efforts of the border police was the lack of vehicles assigned to each fort. Many forts had only one vehicle, usually a run down SUV or pick-up almost in a state of disrepair. Proper equipage became an immediate priority for the BTT, resulting in the delivery of new vehicles, uniforms, weapons and other equipment to the forts. “We constantly emphasized that they open lines of communication with their own chain of command, the Ministry of Interior,” Lt. Lopez noted. “It was important that they start to rely on MOI for issues rather than relying on us for everything.”

Getting the equipment to the forts and keeping it maintained was the greatest challenge following the assessment phase, said GySgt. Shawn Dellinger, Operations SNCOIC. “We showed them how to improvise, to adapt, to utilize the equipment they already had…when a piece of equipment breaks, (how to) keep it maintained and fix it.” From 4-wheel drive vehicles to communications gear, GySgt. Dellinger said the establishment of an effective preventive maintenance program by the border police went a long way in the ensuring the success of the DBE.

Dellinger indicated the lack of NCO leadership among the Iraqi units was the root of the problem that allowed the maintenance and equipment issues to flourish. “There is no staff or NCO leadership when the officers are not around, no enlisted leadership whatsoever. An officer has to make the decision. An officer goes out on patrol, an officer tells them to clean up, to wake up…they don’t make a move without an officer present. If the officer didn’t give approval, they don’t do it….it’s a habit from the old regime,” Dellinger stated. The solution was teaching the border police the concept of the non-commissioned officer. “Our biggest challenge was showing them that we, as staff NCO’s, have responsibility, have leadership, make decisions and go out there to get the mission done without having to have an officer present.” (4)

The training phase started slowly but rapidly gained momentum. The first several days were spent teaching sanitation fundamentals. From trash collection to hygiene trenches, the Leathernecks imparted the philosophy of cleaner, more sanitary workplaces. Operational lessons followed, including instruction on basic patrol fundamentals at the fire team and squad levels. Getting the border police to leave the confines of the border fort and conduct proactive patrols, either by vehicle or afoot was a success in itself. The active patrols were outwardly displaying a law enforcement presence not previously seen on a regular basis.

The BTT also developed leadership courses using the 14 leadership traits taught to Marine officer candidates and recruits, focusing on judgment, initiative, and integrity. Classes on motor transport maintenance, driving techniques, and basic logistics issues helped fill the day, each lesson resulting in a more empowered border policeman.